The Challenge of Closeness: Alain de Botton on Love, Vulnerability, and the Paradox of Avoidance

The hardest thing in life isn’t getting what we want, isn’t even knowing what we want, but knowing what to want. We think we want connection, but as soon as contact reaches deeper than the skin of being, we recoil with the terror of vulnerability. There is no place more difficult to show up than where marrow meets marrow. And yet that is the only place where two people earn the right to use the word “love.” Our avoidance of that terrifying, transcendent place holds up a mirror to our most fundamental beliefs about life and love, about what we deserve and what we are capable of, about reality and the landscape of the possible. That is what Alain de Botton explores in this animated essay probing the psychological machinery of avoidance in intimate relationships — where it comes from, how to live with it, and where it can go if handled with enough conscientiousness and compassion. [embedded content] In The School of Life: An Emotional Education (public library) — the book companion to his wonderful global academy for skillful living — De Botton explores the deeper dimensions of avoidance and how to live with it, both as its proprietor and its partner. Recognizing the paralyzing fear of hurt, rejection, and abandonment at the heart of avoidance, he writes: One of the odder features of relationships is that, in truth, the fear of rejection never ends. It continues, even in quite sane people, on a daily basis, with frequently difficult consequences — chiefly because we refuse to pay it sufficient attention and aren’t trained to spot its counter-intuitive symptoms in others. We haven’t found a winning way to keep admitting just how much reassurance we need. […] Instead of requesting reassurance endearingly and laying out our longing with charm, we have tendencies to mask our needs beneath some tricky behaviors guaranteed to frustrate our ultimate aims. Avoidance is one of the commonest ways of hedging against our fear of rejection and hurt — a coping mechanism for disappointment that we developed when the people first tasked with caring for us let us down. De Botton writes: We grow into avoidant patterns when, in childhood, attempts at closeness ended in degrees of rejection, humiliation, uncertainty, or shame that we were ill-equipped to deal with. We became, without consciously realizing it, determined that such levels of exposure would never happen again. At an early sign of being disappointed, we therefore now understand the need to close ourselves off from pain. We are too scarred to know how to stay around and mention that we are hurt. With an eye to the undertow of vulnerability beneath all avoidant patterns, he adds: If this harsh, graceless behavior could be truly understood for what it is, it would be revealed not as rejection or indifference, but as a strangely distorted, yet very real, plea for tenderness. A central solution to these patterns is to normalize a new and more accurate picture of emotional functioning: to make it clear just how predictable it is to be in need of reassurance, and at the same time, how understandable it is to be reluctant to reveal one’s dependence. We should create room for regular moments, perhaps as often as every few hours, when we can feel unembarrassed and legitimate about asking for confirmation. “I really need you. Do you still want me?” should be the most normal of enquiries. Complement with philosopher Martha Nussbaum on how to live with our human fragility and Hannah Arendt on how to live with the fundamental fear of love’s loss, then revisit Alain de Botton on the importance of breakdowns, what makes a good communicator, and the key to existential maturity.

The hardest thing in life isn’t getting what we want, isn’t even knowing what we want, but knowing what to want. We think we want connection, but as soon as contact reaches deeper than the skin of being, we recoil with the terror of vulnerability. There is no place more difficult to show up than where marrow meets marrow. And yet that is the only place where two people earn the right to use the word “love.”

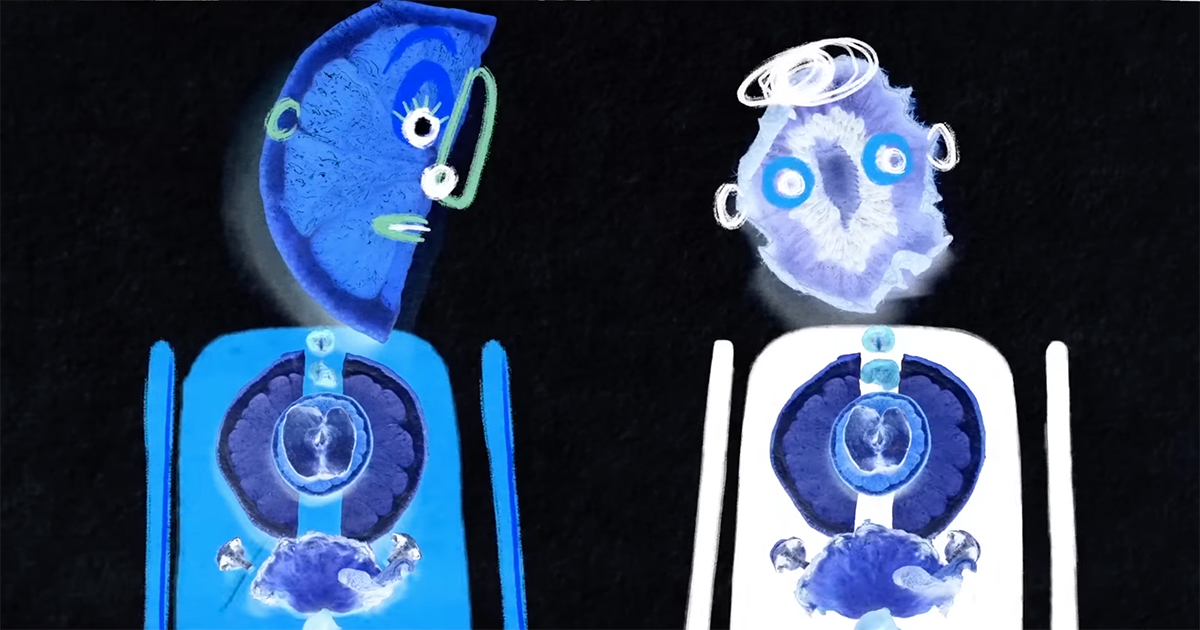

Our avoidance of that terrifying, transcendent place holds up a mirror to our most fundamental beliefs about life and love, about what we deserve and what we are capable of, about reality and the landscape of the possible. That is what Alain de Botton explores in this animated essay probing the psychological machinery of avoidance in intimate relationships — where it comes from, how to live with it, and where it can go if handled with enough conscientiousness and compassion.

[embedded content]

In The School of Life: An Emotional Education (public library) — the book companion to his wonderful global academy for skillful living — De Botton explores the deeper dimensions of avoidance and how to live with it, both as its proprietor and its partner. Recognizing the paralyzing fear of hurt, rejection, and abandonment at the heart of avoidance, he writes:

One of the odder features of relationships is that, in truth, the fear of rejection never ends. It continues, even in quite sane people, on a daily basis, with frequently difficult consequences — chiefly because we refuse to pay it sufficient attention and aren’t trained to spot its counter-intuitive symptoms in others. We haven’t found a winning way to keep admitting just how much reassurance we need.

[…]

Instead of requesting reassurance endearingly and laying out our longing with charm, we have tendencies to mask our needs beneath some tricky behaviors guaranteed to frustrate our ultimate aims.

Avoidance is one of the commonest ways of hedging against our fear of rejection and hurt — a coping mechanism for disappointment that we developed when the people first tasked with caring for us let us down. De Botton writes:

We grow into avoidant patterns when, in childhood, attempts at closeness ended in degrees of rejection, humiliation, uncertainty, or shame that we were ill-equipped to deal with. We became, without consciously realizing it, determined that such levels of exposure would never happen again. At an early sign of being disappointed, we therefore now understand the need to close ourselves off from pain. We are too scarred to know how to stay around and mention that we are hurt.

With an eye to the undertow of vulnerability beneath all avoidant patterns, he adds:

If this harsh, graceless behavior could be truly understood for what it is, it would be revealed not as rejection or indifference, but as a strangely distorted, yet very real, plea for tenderness.

A central solution to these patterns is to normalize a new and more accurate picture of emotional functioning: to make it clear just how predictable it is to be in need of reassurance, and at the same time, how understandable it is to be reluctant to reveal one’s dependence. We should create room for regular moments, perhaps as often as every few hours, when we can feel unembarrassed and legitimate about asking for confirmation. “I really need you. Do you still want me?” should be the most normal of enquiries.

Complement with philosopher Martha Nussbaum on how to live with our human fragility and Hannah Arendt on how to live with the fundamental fear of love’s loss, then revisit Alain de Botton on the importance of breakdowns, what makes a good communicator, and the key to existential maturity.