Taking Risk Is No Longer Necessary, but That Is a Problem

Commentary Taking risks is no longer necessary to make a return on your savings. Not long ago, “cash is trash” was a common theme as savings accounts yielded zero. Of course, such was the intent of the Federal Reserve following the financial crisis of 2008–09 in the hope that inflating asset prices would trickle down into economic growth. Given the economy is driven by consumption, the Fed believed that promoting asset inflation would lead to increased confidence, thereby creating economic growth. Such was the exact point made in 2010 by former Fed chair Ben Bernanke: “Easier financial conditions will promote economic growth. For example, lower mortgage rates will make housing more affordable and allow more homeowners to refinance. Lower corporate bond rates will encourage investment. And higher stock prices will boost consumer wealth and help increase confidence, which can also spur spending.” Unfortunately, the result was not as advertised. Instead, economic growth stagnated, and the wealth gap exploded. (Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis / RealInvestmentAdvice.com chart) To put this in better perspective, the top 10 percent of households now control 68 percent of all wealth. The following 40 percent have 29 percent, with the bottom 50 percent owning just 3 percent. (Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis / RealInvestmentAdvice.com chart) This data make it easy to understand why there is such an outcry for socialism today. A New Threat Arises However, there is a problem with the Fed’s premise. Given that the top 10 percent of Americans own most assets, there is a declining propensity to spend money. Once those individuals bought a house(s), furnished them, bought cars, traveled, etc., there was no need to continue spending at accelerated rates. Therefore, the income of the top 10–20 percent wound up in savings. Conversely, the bottom 80 percent live paycheck to paycheck. This is why consumer debt has exploded to maintain the standard of living. (Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis / RealInvestmentAdvice.com chart) Of course, the side effect of monetary interventions was the deformation of asset markets. Those actions led to the top 10 percent of income earners owning 85 percent of the financial market wealth. (Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis / RealInvestmentAdvice.com chart) If there is good news in that chart, it is only that the bear market of 2022 had minimal impact on the bottom 90 percent of Americans due to a lack of risk exposure. (Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis / RealInvestmentAdvice.com chart) However, the Fed now faces a new threat. Paradox of Thrift As noted, the Fed’s original objective was to lower rates on savings to the point where individuals would seek other alternatives. The reason is the “paradox of thrift,” which, according to Investopedia, states: “The paradox of thrift, or paradox of savings, is an economic theory that posits that personal savings are a net drag on the economy during a recession.” The theory, posited by the economist John Maynard Keynes, suggested that the proper response to an economic recession was more spending, more risk-taking, and fewer savings. Such was the basis of Bernanke’s decision to drop interest rates to zero and flood the economy with monetary stimulus following the financial crisis of 2008–09. However, dropping rates to zero boosted asset prices, but didn’t translate into organic economic growth or inflation. Inflation and economic growth exploded only when the Fed sent checks directly to those bottom 80 percent of income earners living paycheck to paycheck. (Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis / RealInvestmentAdvice.com chart) With the fiscal stimulus now over, growth rates are returning to their organic trend. Notably, today’s growth rate remains below the long-term trend growth levels pre-2000 and 2007. (Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis / RealInvestmentAdvice.com chart) However, while the Fed’s actions kept the economy from a potentially far worse recession, it is now faced with a potentially far worse problem. With savings rates beginning to push 5 percent in money market accounts and Treasury bills, savers are now being given an alternative to taking risks. Unfortunately, the paradox of thrift puts the Fed in a battle between needing to hike rates to lower inflation or, once again, forcing money out of savings to stimulate economic activity. Surging Money Market Balances Are Problematic There is currently $5 trillion sitting in money market funds, according to the Federal Reserve data. (Note that balances increase each time the Fed starts a rate-hike campaign.) (Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis / RealInvestmentAdvice.com chart) The Fed faces a tough choice if the paradox of thrift does detract from economic growth. Currently, it is okay with hiking rates to combat inflation by incentivizing savers away from taking risks and slowing economi

Commentary

Taking risks is no longer necessary to make a return on your savings.

Not long ago, “cash is trash” was a common theme as savings accounts yielded zero. Of course, such was the intent of the Federal Reserve following the financial crisis of 2008–09 in the hope that inflating asset prices would trickle down into economic growth. Given the economy is driven by consumption, the Fed believed that promoting asset inflation would lead to increased confidence, thereby creating economic growth. Such was the exact point made in 2010 by former Fed chair Ben Bernanke:

“Easier financial conditions will promote economic growth. For example, lower mortgage rates will make housing more affordable and allow more homeowners to refinance. Lower corporate bond rates will encourage investment. And higher stock prices will boost consumer wealth and help increase confidence, which can also spur spending.”

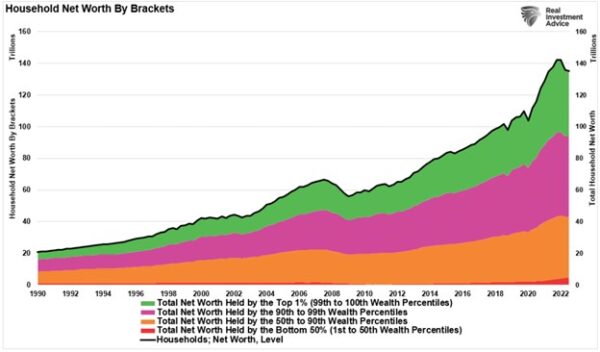

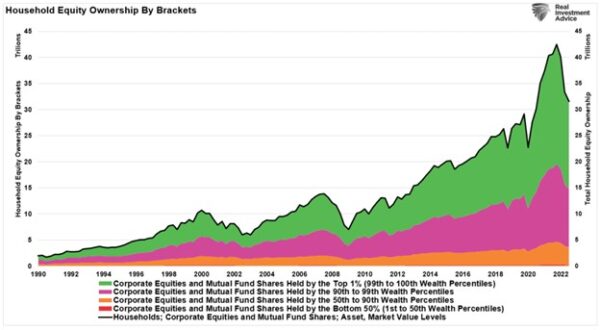

Unfortunately, the result was not as advertised. Instead, economic growth stagnated, and the wealth gap exploded.

(Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis / RealInvestmentAdvice.com chart)

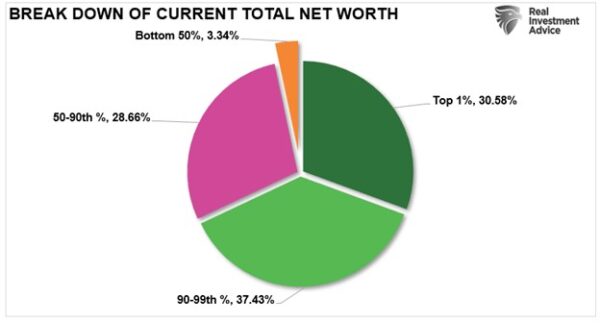

To put this in better perspective, the top 10 percent of households now control 68 percent of all wealth. The following 40 percent have 29 percent, with the bottom 50 percent owning just 3 percent.

(Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis / RealInvestmentAdvice.com chart)

This data make it easy to understand why there is such an outcry for socialism today.

A New Threat Arises

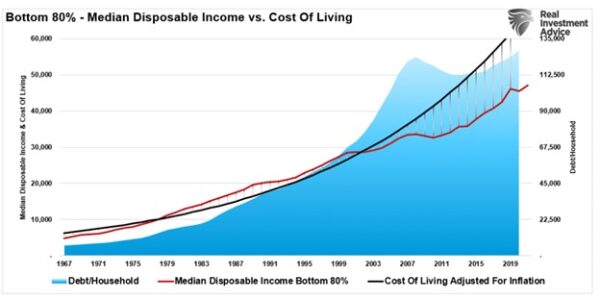

However, there is a problem with the Fed’s premise. Given that the top 10 percent of Americans own most assets, there is a declining propensity to spend money. Once those individuals bought a house(s), furnished them, bought cars, traveled, etc., there was no need to continue spending at accelerated rates. Therefore, the income of the top 10–20 percent wound up in savings. Conversely, the bottom 80 percent live paycheck to paycheck. This is why consumer debt has exploded to maintain the standard of living.

(Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis / RealInvestmentAdvice.com chart)

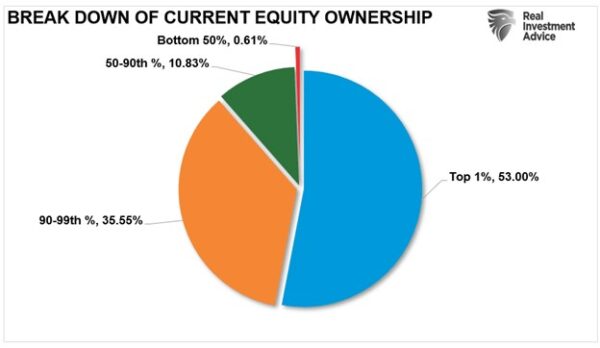

Of course, the side effect of monetary interventions was the deformation of asset markets. Those actions led to the top 10 percent of income earners owning 85 percent of the financial market wealth.

(Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis / RealInvestmentAdvice.com chart)

If there is good news in that chart, it is only that the bear market of 2022 had minimal impact on the bottom 90 percent of Americans due to a lack of risk exposure.

(Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis / RealInvestmentAdvice.com chart)

However, the Fed now faces a new threat.

Paradox of Thrift

As noted, the Fed’s original objective was to lower rates on savings to the point where individuals would seek other alternatives. The reason is the “paradox of thrift,” which, according to Investopedia, states:

“The paradox of thrift, or paradox of savings, is an economic theory that posits that personal savings are a net drag on the economy during a recession.”

The theory, posited by the economist John Maynard Keynes, suggested that the proper response to an economic recession was more spending, more risk-taking, and fewer savings. Such was the basis of Bernanke’s decision to drop interest rates to zero and flood the economy with monetary stimulus following the financial crisis of 2008–09.

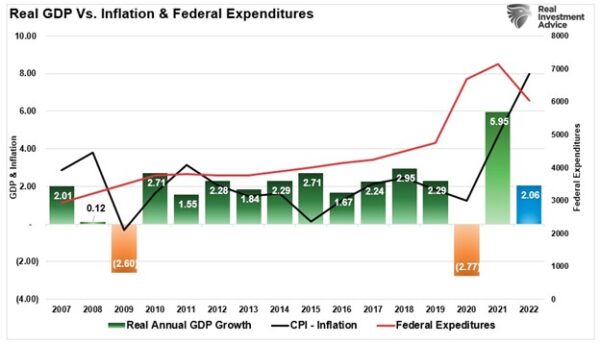

However, dropping rates to zero boosted asset prices, but didn’t translate into organic economic growth or inflation. Inflation and economic growth exploded only when the Fed sent checks directly to those bottom 80 percent of income earners living paycheck to paycheck.

(Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis / RealInvestmentAdvice.com chart)

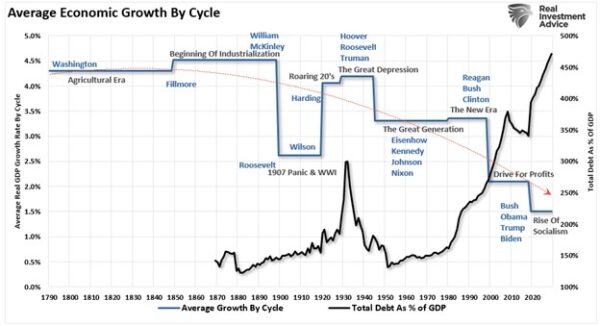

With the fiscal stimulus now over, growth rates are returning to their organic trend. Notably, today’s growth rate remains below the long-term trend growth levels pre-2000 and 2007.

(Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis / RealInvestmentAdvice.com chart)

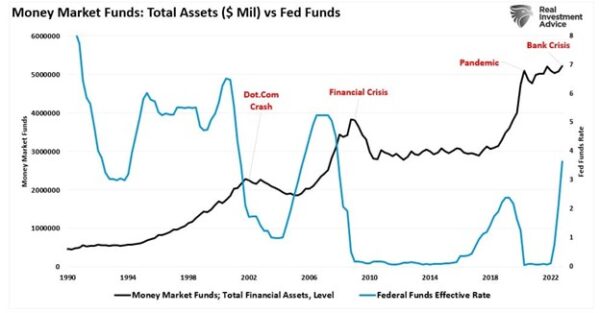

However, while the Fed’s actions kept the economy from a potentially far worse recession, it is now faced with a potentially far worse problem. With savings rates beginning to push 5 percent in money market accounts and Treasury bills, savers are now being given an alternative to taking risks.

Unfortunately, the paradox of thrift puts the Fed in a battle between needing to hike rates to lower inflation or, once again, forcing money out of savings to stimulate economic activity.

Surging Money Market Balances Are Problematic

There is currently $5 trillion sitting in money market funds, according to the Federal Reserve data. (Note that balances increase each time the Fed starts a rate-hike campaign.)

(Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis / RealInvestmentAdvice.com chart)

The Fed faces a tough choice if the paradox of thrift does detract from economic growth.

Currently, it is okay with hiking rates to combat inflation by incentivizing savers away from taking risks and slowing economic growth. However, the problem comes when the recession occurs. At that juncture, the Fed must choose between fighting the economic downturn or cutting interest rates to zero, forcing trillions of dollars from savings back into the market.

Unfortunately, since most of these savings belong to the top 10 percent of income earners, cutting rates will exacerbate the wealth gap further.

While the Federal Reserve occasionally feigns concern over the wealth gap and speculative market risks, the problem remains the inability to facilitate organic economic growth.

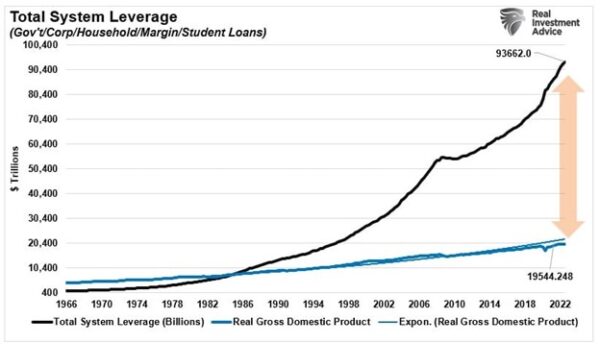

Given the debt required to sustain current economic growth, the Fed has no choice but to continue monetizing the federal debt indefinitely.

The Choice Between Two Evils

This, in our view, leaves only two possible outcomes from here, which are not good:

- Powell & Co. reverse rates to zero. As aging demographics strain the pension and social welfare systems, the debt will continue to stifle inflation and economic growth. The cycle that started nearly 40 years ago will continue as the United States adopts the “Japan syndrome.”

- The second outcome is far worse: an economic decoupling that leads to a massive deleveraging process. That event started in 2008, but was cut short by central bank interventions. In 2020, the Fed arrested the deleveraging process once again. Both events led to an even more debt-laden system.

(Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis / RealInvestmentAdvice.com chart)

We now know that surging debt and deficits inhibit organic growth. The massive debt levels added onto the backs of taxpayers will only ensure the Fed will eventually get forced back to zero bounds.

(Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis / RealInvestmentAdvice.com chart)

While taking risks is no longer necessary given current yields on money markets, if you are a saver, I would suggest locking in rates sooner than later. History is pretty clear about future outcomes from the Fed’s current actions.

Supporting economic growth through increasing debt levels only makes sense if “growth at all costs” uniformly benefits all citizens. Unfortunately, we are finding a big difference between growth and prosperity.

An inflation policy that minimizes concern for debt burdens while accelerating the growth of those burdens is taking a severe toll on economic and social stability.

The United States is not immune to social disruptions. The source of these problems is compounding due to the public’s failure to appreciate why it is happening. Until the Fed’s policies are publicly discussed and reconsidered, the policies will remain, and the problems will grow.