Sundogs and the Sacred Geometry of Wonder: The Science of the Atmospheric Phenomenon That Inspired Hilma af Klint

On the morning of April 10, 1535, the skies of Stockholm came ablaze with three suns intersected by several bright circles and arcs. Awestruck, people took it for a sign from God — a benediction on the new Lutheran faith that had taken hold of Sweden. Catholics took it for the opposite — punishment lashed on King Gustav Vasa for having ushered in the Protestant Reformation a decade earlier. What the pious were actually witnessing was a parhelion, from the Greek for “beside the sun,” also known as sundog or mock sun — an atmospheric optical phenomenon caused by the refraction of sunlight through ice crystals in high, cold cirrus or cirrostratus clouds, or in moist ground-level clouds known as diamond dust. Vädersolstavlan, 1535 / 1636 Parhelia have staggered the human imagination since the dawn of our common record, epochs before empiricism could cast its ray of illumination upon their mystery. “Two mock suns rose with the sun and followed it all through the day until sunset,” Aristotle wrote in the oldest known account of the phenomenon. “Those that affirm they witnessed this prodigy are neither few nor unworthy of credit, so that there is more reason for investigation than incredulity,” Cicero wrote in urging the Roman Senate to examine “the nature of the parhelion.” A generation after him, Seneca included sundogs in his epochal Naturales Quaestiones. They appear in the Old Farmer’s Almanac as omens of storms. That awe-smiting April in Stockholm, the Chancellor and Lutheran scholar Olaus Petri commissioned a painting of the wondrous event — a painting that became the epicenter of a political controversy when the King took it as an insult and narrowly spared Petri capital punishment. Known as Vädersolstavlan — Swedish for “The Sundog Painting” — it is considered the oldest known depiction of sundogs. More than three centuries later, a little girl beheld the enormous painting in a Swedish cathedral, absorbing its magic and its mystery into the cabinet of curiosities that is a child’s imagination. Half a lifetime and a revelation later, Hilma af Klint (October 26, 1862–October 21, 1944) would draw on it in many of her own immense and unexampled paintings reckoning with the hidden strata of reality. Art by Hilma af Klint from her series Childhood Paintings, 1907. Because of the conditions they requires, perihelia are among the least common and most dramatic of atmospheric optical phenomena. They appear when flat hexagonal ice crystals drift into a horizontal orientation relative to the surface of the Earth and catch sunlight, acting as prisms to refract rays sideways with a minimum deflection of 22°. This is why sundogs appear in pairs at around 22° on either side of the sun, and why they are often accompanied — as they were that spring morning in 1535 — by a 22° halo forming a ring at the same angular distance from the sun as the sundogs, thus appearing to intersect and connect all three stars into a luminous orrery of circles. It is difficult to behold its exquisite geometry and not feel it to be sacred. It is difficult not to see these geometric elements as an organizing principle of Hilma af Klint’s mystical paintings. Art, after all, might just be our sensemaking mechanism for wonder. In this respect, it is not the opposite of science but its twin.

On the morning of April 10, 1535, the skies of Stockholm came ablaze with three suns intersected by several bright circles and arcs. Awestruck, people took it for a sign from God — a benediction on the new Lutheran faith that had taken hold of Sweden. Catholics took it for the opposite — punishment lashed on King Gustav Vasa for having ushered in the Protestant Reformation a decade earlier.

What the pious were actually witnessing was a parhelion, from the Greek for “beside the sun,” also known as sundog or mock sun — an atmospheric optical phenomenon caused by the refraction of sunlight through ice crystals in high, cold cirrus or cirrostratus clouds, or in moist ground-level clouds known as diamond dust.

Parhelia have staggered the human imagination since the dawn of our common record, epochs before empiricism could cast its ray of illumination upon their mystery. “Two mock suns rose with the sun and followed it all through the day until sunset,” Aristotle wrote in the oldest known account of the phenomenon. “Those that affirm they witnessed this prodigy are neither few nor unworthy of credit, so that there is more reason for investigation than incredulity,” Cicero wrote in urging the Roman Senate to examine “the nature of the parhelion.” A generation after him, Seneca included sundogs in his epochal Naturales Quaestiones. They appear in the Old Farmer’s Almanac as omens of storms.

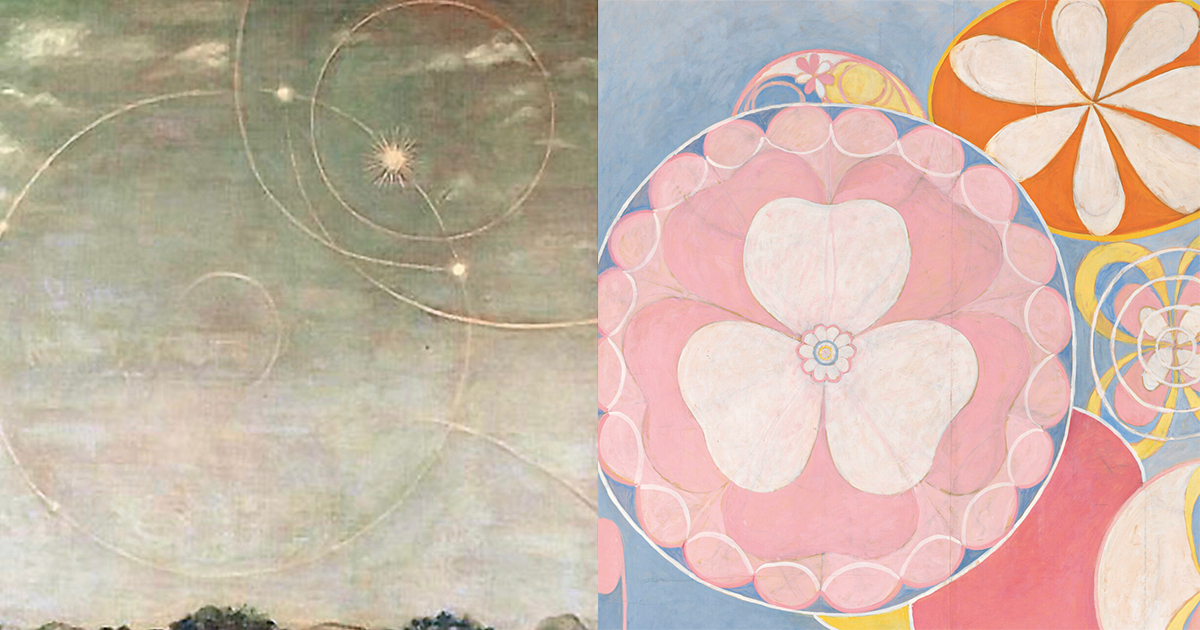

That awe-smiting April in Stockholm, the Chancellor and Lutheran scholar Olaus Petri commissioned a painting of the wondrous event — a painting that became the epicenter of a political controversy when the King took it as an insult and narrowly spared Petri capital punishment. Known as Vädersolstavlan — Swedish for “The Sundog Painting” — it is considered the oldest known depiction of sundogs.

More than three centuries later, a little girl beheld the enormous painting in a Swedish cathedral, absorbing its magic and its mystery into the cabinet of curiosities that is a child’s imagination. Half a lifetime and a revelation later, Hilma af Klint (October 26, 1862–October 21, 1944) would draw on it in many of her own immense and unexampled paintings reckoning with the hidden strata of reality.

Because of the conditions they requires, perihelia are among the least common and most dramatic of atmospheric optical phenomena. They appear when flat hexagonal ice crystals drift into a horizontal orientation relative to the surface of the Earth and catch sunlight, acting as prisms to refract rays sideways with a minimum deflection of 22°. This is why sundogs appear in pairs at around 22° on either side of the sun, and why they are often accompanied — as they were that spring morning in 1535 — by a 22° halo forming a ring at the same angular distance from the sun as the sundogs, thus appearing to intersect and connect all three stars into a luminous orrery of circles. It is difficult to behold its exquisite geometry and not feel it to be sacred. It is difficult not to see these geometric elements as an organizing principle of Hilma af Klint’s mystical paintings. Art, after all, might just be our sensemaking mechanism for wonder. In this respect, it is not the opposite of science but its twin.