Is This Finally Some Tolerable Inflation News?

Commentary For reasons I don’t get, the whole of financial markets is obsessed with the Consumer Price Index (CPI) but the Producer Price Index (PPI) is largely ignored. It hardly makes the headlines. That makes no sense because everything we consume (except maybe bugs) has to be produced. The consumer experience of inflation is downstream from the producer experience of inflation. That’s because we live in an advanced and complex economy with long production structures. The PPI just came out and presented what is really the first seemingly solid good news in two years. The index for final demand actually declined 0.5 percent in March. Over twelve months the increase is 2.7 percent. That’s not yet the target of 2 percent but it is close. And this pertains to both goods and services. In the entire list of producer prices, I don’t spot anything that was hot in March. This is good news for consumers. It means that prices will likely settle by summer and certainly by the fall (if we have any money left to buy them). The relationship between producer and consumer prices is well established empirically. We’ve seen this playing itself out in the lockdown years. The PPI pulled along the CPI at every stage. This only makes sense. It also means that producers have borne the brunt of the inflation bout. (Data: Federal Reserve Economic Data [FRED], St. Louis Fed; Chart: Jeffrey A. Tucker)Now, let’s dig a bit deeper. Why might this be happening and does the Fed deserve some credit? It certainly does deserve some credit for this. But in the course of battling inflation, it has also undertaken two steps without precedent: the largest decline in the money supply in nearly 100 years and the largest and fastest rate increases on record. The impact of those policies has not been restricted to prices only. Money in a market economy is never neutral to production decisions and structures. Its value, both in spending and load markets, impacts the whole of the system. The Fed might imagine that it is moving only one piece on the chessboard but these actors have a huge range of effects, most of which are unpredictable. A large and fast increase in rates combined with a falling money supply can arrest inflationary momentum. We’ve seen that lately and we saw that also in the late 1970s. It’s pretty much the whole means by which the Fed can course correct. When they make a major screw-up like they did in 2020–21, the only way to keep the whole system from blowing up is to impose this kind of pain. On the other hand, it is rather troubling that the Fed itself has either not admitted why it is doing this or does not entirely understand the relationship between its loose-money policies and the effects on prices and production structures. Everything we’ve heard from the Fed suggests that its plan for the better part of two years has been to cool off the economy by deliberately creating recessionary conditions, while hoping for a so-called soft landing. This is pretty much the opposite of what happened in the late 1970s. Volcker nowhere attempted to create recession. His goal was to end money expansion and let policy makers take it from there. It was the insight of George Gilder and others among the supply-side crowd that the best possible weapon against inflation is not recession but new economic growth. That is why they pushed tax cuts and deregulation. That way inflation dies through both the monetary side and the growth side. They knew it. By rejecting the Keynesian paradigm of austerity, they believed that dramatic economic growth would actually have the effect of cooling off price increases. And they turned out to be absolutely correct. Nothing like this is happening now. The Fed is creating all the conditions that lead to recession while the administration and lawmakers have lost all taste for policies that would spur economic growth. I simply cannot remember the last time I heard any lawmaker talking about dramatic tax cuts. That doesn’t even seem to be on the table. As for real spending cuts to go with them, forget about it. All the policy momentum is in the opposite direction. We’ve got a ruling-class longing for population-wide austerity, restriction, deprivation, and the imposition of ever less prosperity and growth. The entire climate-change agenda is nothing but that but it is only a beginning. There is alive in the land a longing for a much more primitive way of life. And imposing it by force! The latest PPI trends, then, need to be understood in that context. It very well could be that these price trends represent not a monetary drive to lower inflation but actually the onset of a real recession. After all, when demand falls, producers cut back, and consumers start restricting their spending, the result will be falling prices all else being equal. There is some evidence that this might be the underlying cause for the decline in producer prices. If so, that’s a heck of a trade-off. It’s one thing to get infla

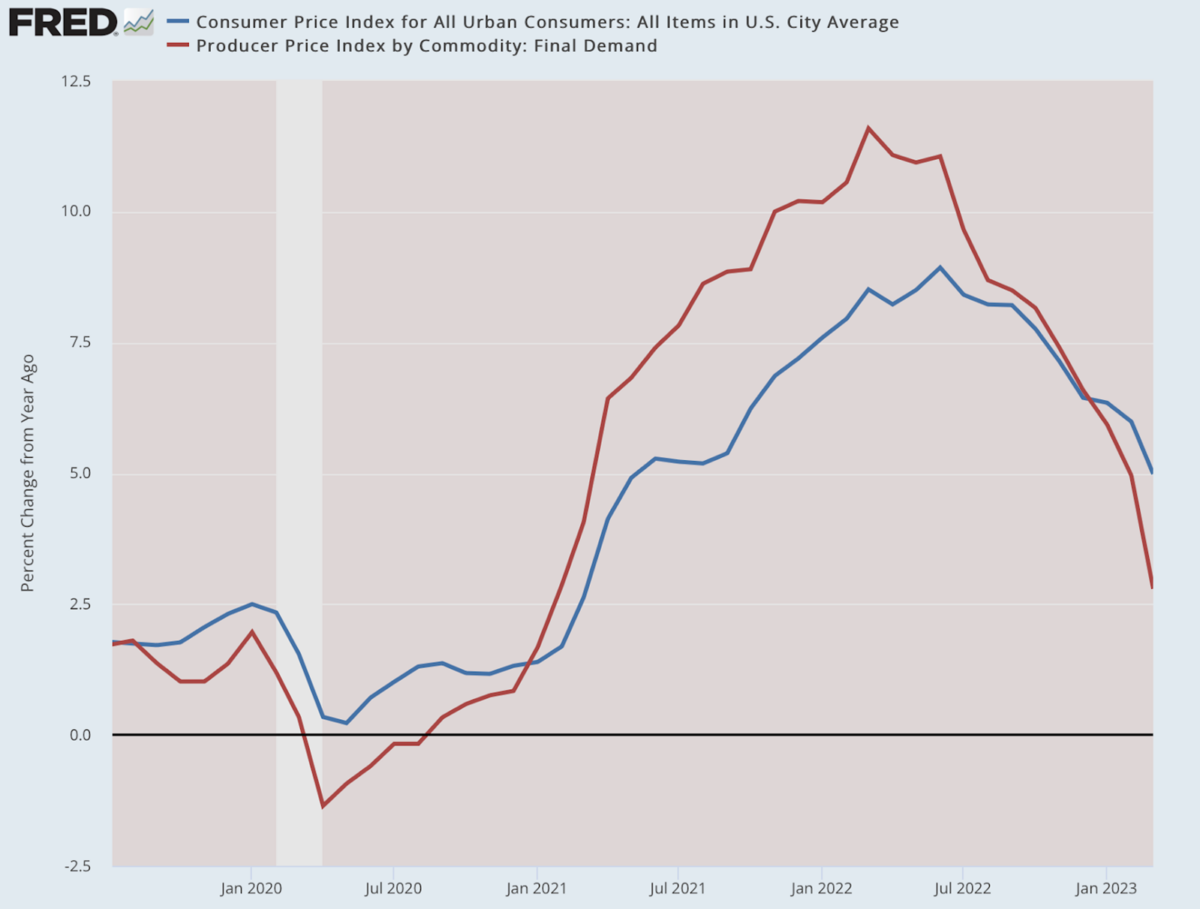

For reasons I don’t get, the whole of financial markets is obsessed with the Consumer Price Index (CPI) but the Producer Price Index (PPI) is largely ignored. It hardly makes the headlines.

That makes no sense because everything we consume (except maybe bugs) has to be produced. The consumer experience of inflation is downstream from the producer experience of inflation. That’s because we live in an advanced and complex economy with long production structures.

The PPI just came out and presented what is really the first seemingly solid good news in two years. The index for final demand actually declined 0.5 percent in March. Over twelve months the increase is 2.7 percent. That’s not yet the target of 2 percent but it is close. And this pertains to both goods and services. In the entire list of producer prices, I don’t spot anything that was hot in March.

This is good news for consumers. It means that prices will likely settle by summer and certainly by the fall (if we have any money left to buy them). The relationship between producer and consumer prices is well established empirically. We’ve seen this playing itself out in the lockdown years. The PPI pulled along the CPI at every stage. This only makes sense. It also means that producers have borne the brunt of the inflation bout.

Now, let’s dig a bit deeper. Why might this be happening and does the Fed deserve some credit? It certainly does deserve some credit for this. But in the course of battling inflation, it has also undertaken two steps without precedent: the largest decline in the money supply in nearly 100 years and the largest and fastest rate increases on record. The impact of those policies has not been restricted to prices only.

Money in a market economy is never neutral to production decisions and structures. Its value, both in spending and load markets, impacts the whole of the system. The Fed might imagine that it is moving only one piece on the chessboard but these actors have a huge range of effects, most of which are unpredictable.

A large and fast increase in rates combined with a falling money supply can arrest inflationary momentum. We’ve seen that lately and we saw that also in the late 1970s. It’s pretty much the whole means by which the Fed can course correct. When they make a major screw-up like they did in 2020–21, the only way to keep the whole system from blowing up is to impose this kind of pain.

On the other hand, it is rather troubling that the Fed itself has either not admitted why it is doing this or does not entirely understand the relationship between its loose-money policies and the effects on prices and production structures.

Everything we’ve heard from the Fed suggests that its plan for the better part of two years has been to cool off the economy by deliberately creating recessionary conditions, while hoping for a so-called soft landing. This is pretty much the opposite of what happened in the late 1970s. Volcker nowhere attempted to create recession. His goal was to end money expansion and let policy makers take it from there.

It was the insight of George Gilder and others among the supply-side crowd that the best possible weapon against inflation is not recession but new economic growth. That is why they pushed tax cuts and deregulation. That way inflation dies through both the monetary side and the growth side. They knew it. By rejecting the Keynesian paradigm of austerity, they believed that dramatic economic growth would actually have the effect of cooling off price increases. And they turned out to be absolutely correct.

Nothing like this is happening now. The Fed is creating all the conditions that lead to recession while the administration and lawmakers have lost all taste for policies that would spur economic growth. I simply cannot remember the last time I heard any lawmaker talking about dramatic tax cuts. That doesn’t even seem to be on the table. As for real spending cuts to go with them, forget about it.

All the policy momentum is in the opposite direction. We’ve got a ruling-class longing for population-wide austerity, restriction, deprivation, and the imposition of ever less prosperity and growth. The entire climate-change agenda is nothing but that but it is only a beginning. There is alive in the land a longing for a much more primitive way of life. And imposing it by force!

The latest PPI trends, then, need to be understood in that context. It very well could be that these price trends represent not a monetary drive to lower inflation but actually the onset of a real recession. After all, when demand falls, producers cut back, and consumers start restricting their spending, the result will be falling prices all else being equal. There is some evidence that this might be the underlying cause for the decline in producer prices.

If so, that’s a heck of a trade-off. It’s one thing to get inflation under control. It’s something else to create conditions that actually lead to economic depression. It’s not entirely impossible that this might be what we are seeing unfold here.

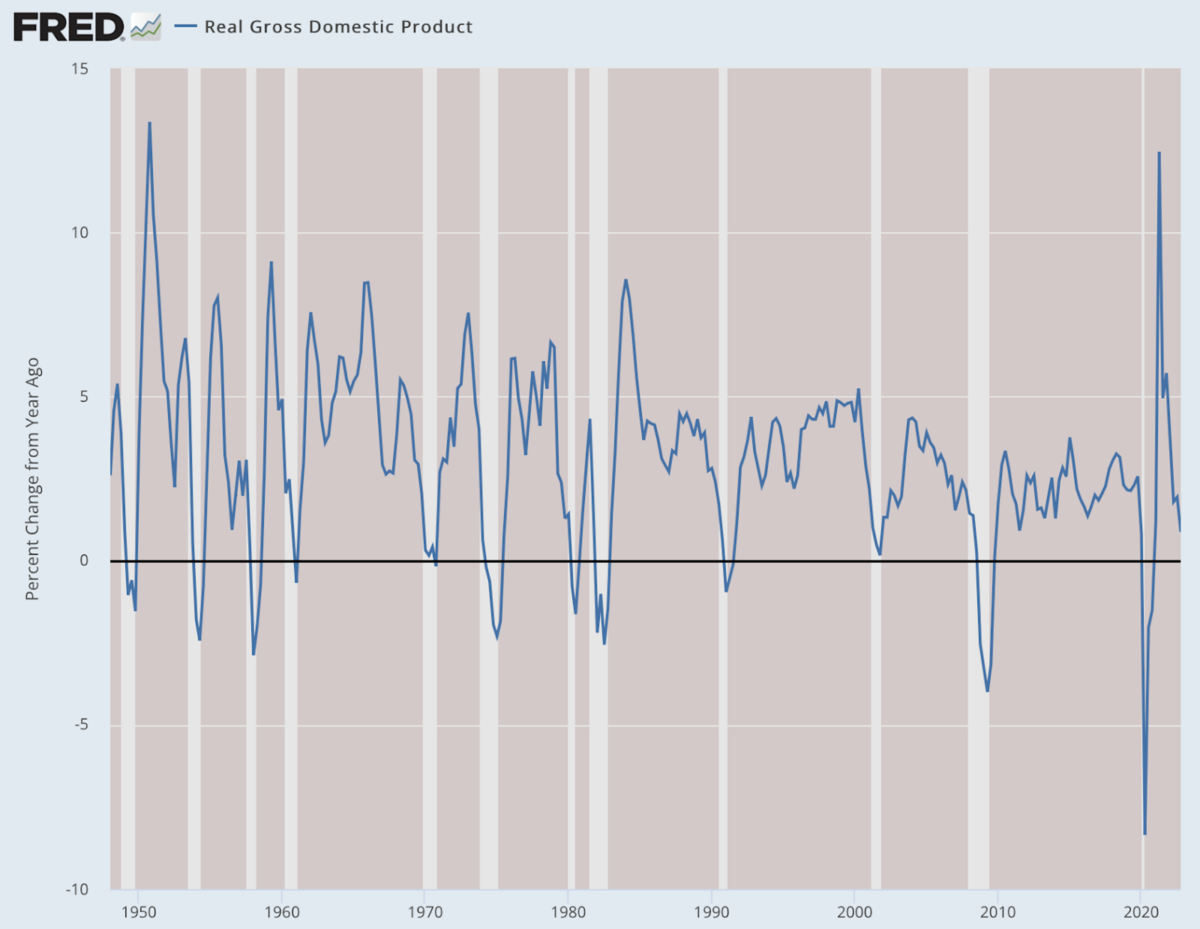

Despite all the talk of strong labor markets, we’ve yet to see labor force participation come back to pre-lockdown levels. The real GDP is not recovered nor real income. Indeed, there is every sign that recession might be right around the corner or already arrived (if we ever really recovered from 2020). The world we live in today is nothing like the rip-roaring times of the 1950s or the 1980s. Our whole sense of what a good economy is has been dramatically dumbed down.

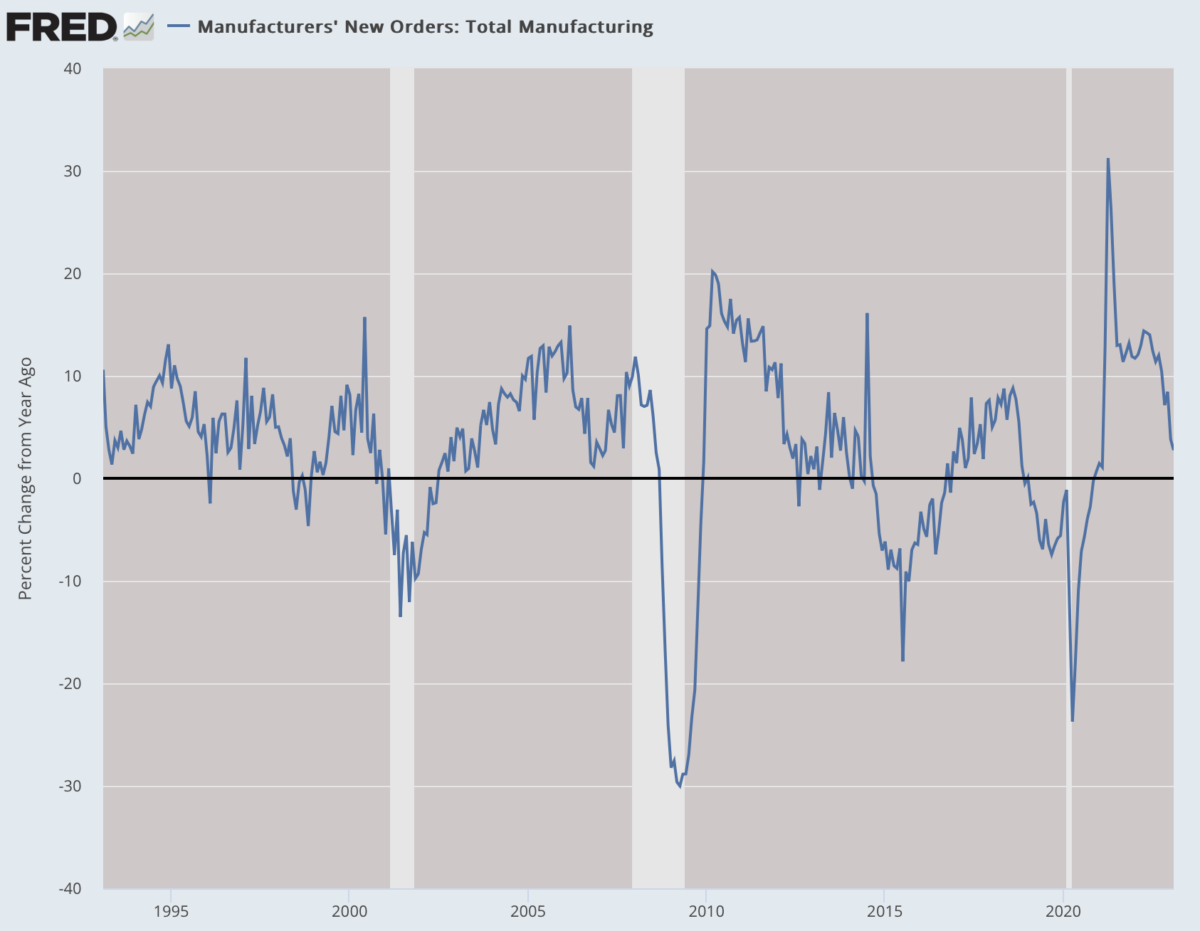

As much as I would like to celebrate the PPI this morning, and credit the Fed for its good work, my instincts tell me to look more carefully. Data on, for example, manufacturing points to the onset of hard times.

What we might be seeing is not the end of inflation as such but the onset of a dying path for economic growth. Killing inflation by killing the economy itself doesn’t seem like a good plan, especially when no one in charge has any taste for reviving American enterprise.

We desperately need the supply-siders back!